How to Write a Good Research Statement: Insights from the Hiring Committee

I recently finished reviewing a stack of forty applications for a tenure-track position.

The cover letters were mostly standard; the CVs were competent.

The decision to interview a candidate often hinged entirely on the research statement.

This document serves as the primary filter for hiring committees at research-intensive institutions.

It distinguishes the candidates who are ready to lead a lab or research agenda from those who are still operating like graduate students.

I have observed that learning how to write a good research statement is less about summarizing past achievements and more about projecting a viable, funded future.

Here is how I approach this critical document and the specific pitfalls I look for when evaluating candidates.

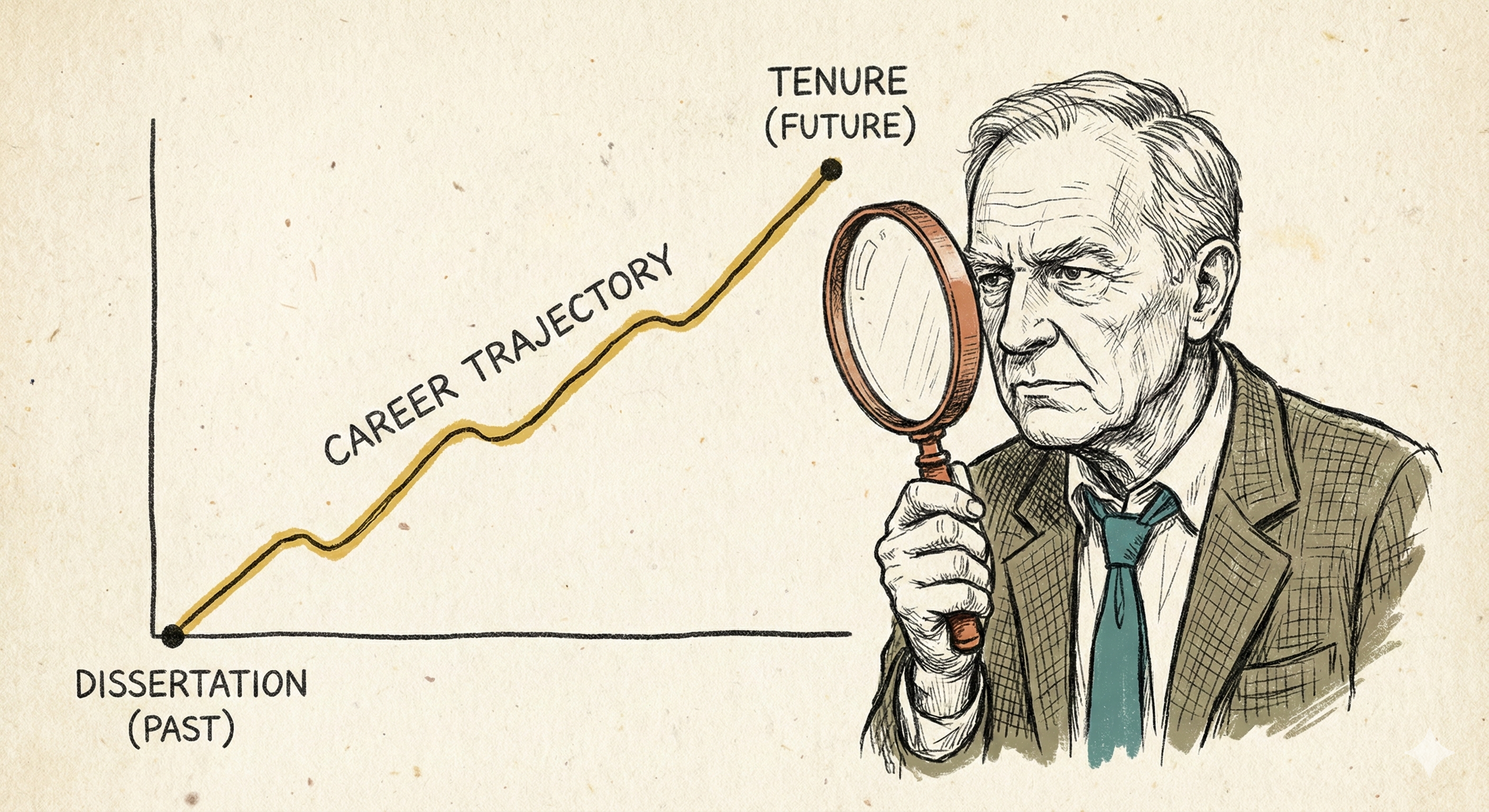

The Core Function: Trajectory Over Archive

A common misconception among early-career academics is that the research statement is an archive of what they have already done.

In my experience, this approach is fatal.

When I sit on a committee, I do not read a statement to learn what you did for your dissertation; I read it to determine if you are tenurable.

The university makes a significant financial investment in a new faculty member.

They need assurance that this investment will yield returns in the form of grants, publications, and prestige five years from now.

Therefore, the most effective statements I see function as a trajectory.

They use the past only as evidence that the candidate can deliver on the future.

My rule of thumb is simple: the past supports the future, but it does not dominate it.

Common Mistakes I See in Rejected Applications

I consistently observe three specific errors that cause candidates to lose points during the review process.

1. The Dissertation Dump

Many candidates devote three pages to the minutiae of their dissertation and one paragraph to their future work.

This signals to the committee that the candidate is looking backward rather than forward.

I prefer to see a balanced structure; perhaps 30% on the dissertation context and 70% on the evolution of that work into new projects.

2. The Jargon Fortress

I often review files for departments adjacent to my own.

If a candidate uses niche terminology without context, they isolate the members of the committee who are not specialists in that exact sub-field.

I found that the strongest applicants defined their terms early; they invited the generalist reader into the conversation rather than locking them out.

3. The "Next Step" Ambiguity

Vague assertions about "continuing research" are insufficient.

I look for specific, concrete details about the next project.

This includes potential funding sources, specific journals for publication, and the precise questions the research will answer.

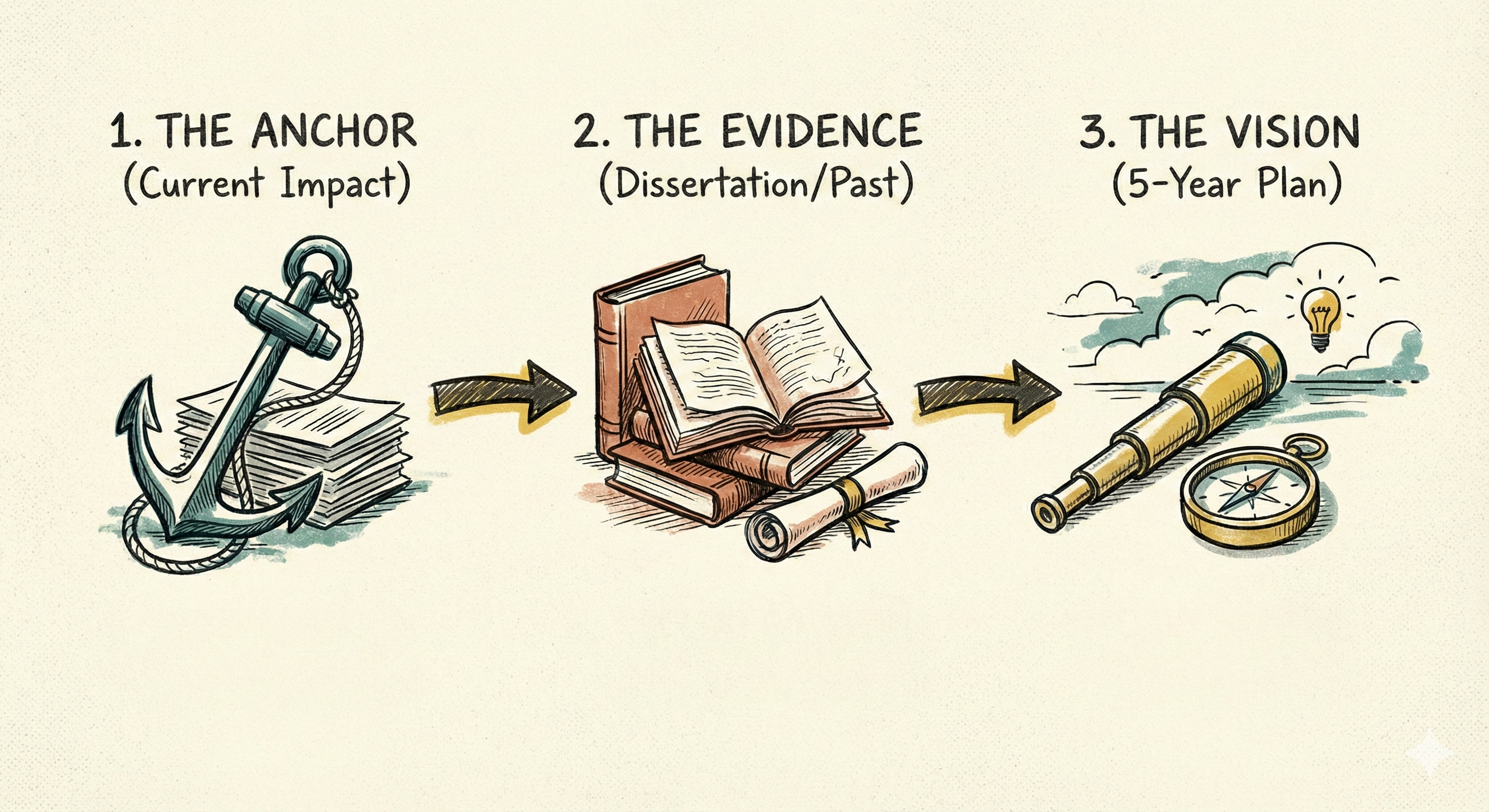

My Framework for Structuring the Narrative

When I advise candidates on structuring this document, I rely on a three-part framework that mirrors the tenure timeline.

This structure provides the committee with exactly the information they need to visualize the candidate as a colleague.

Part 1: The "So What"

I begin with a broad, accessible paragraph that anchors the research in a significant problem.

This section answers the question: "Why does this matter?"

I have found that starting with the impact rather than the methodology hooks the reader immediately.

It demonstrates that the candidate understands the broader implications of their work.

Part 2: The Evidence

This section covers the dissertation or postdoctoral work.

However, I frame it specifically as the foundation for the future.

I focus on the skills acquired, the methodologies mastered, and the publications cemented during this phase.

This serves as the "proof of concept" that the candidate is capable of executing complex projects.

Part 3: The 5-Year Plan (The Vision)

This is the most critical section.

I outline exactly what I plan to achieve in the years leading up to the tenure review.

I break this down into two distinct future projects:

- Project A: The immediate next step (the second book or the next grant series).

- Project B: The long-term, high-risk/high-reward inquiry.

Including specific names of grant agencies (e.g., NSF, NIH, NEH) is highly effective.

It shows the committee that I have already thought about how to fund the work.

Tailoring for the Institution

One strategy that consistently yields positive results is adjusting the statement based on the institution's Carnegie Classification.

When I apply to R1 institutions, I emphasize external funding and high-impact publications.

The narrative focuses on how my lab or research group will become a leader in the field.

Conversely, when I target teaching-focused institutions (PUIs), I shift the narrative.

I explain how undergraduates will be involved in the research process.

I demonstrate that my research is feasible with a heavy teaching load and limited resources.

Ignoring the context of the hiring institution is a quick way to be placed in the "no" pile.

Final Thoughts on Execution

The research statement is an exercise in professional projection.

It requires the candidate to step out of the role of a student and into the role of a peer.

I have found that the most successful candidates write with authority; they state what they will do, not what they hope to do.

If your current draft feels like a summary of your graduate school years, it likely needs a revision.

Focus on the horizon.

Get Your Research Statement Reviewed

Not sure if your research statement is hitting the mark? Get a free application audit from someone who sits on hiring committees and knows exactly what they're looking for.

Get a Free Application Audit